Day 75, Saturday 3rd June 2006Ban Pa Do Tha, near Umphang, Tak Province, ThailandIn some places around the world, you can grow up and understand most things around you. It's a shame I'm not one of them.

What I mean is, for some kids, you know what your house is made out of, how decisions around you are made, the name of everyone in your village, your friends and how to look after the animals that provide your food. I can look back on my childhood and realise that I had a lot of faith in things I could not comprehend: electricity, state welfare, innoculation, curriculum, television etc. Most kids are encouraged, rightly or wrongly, to have faith in their parents and the world around them. Developing autonomy might not be a high priority for a five year old, but you have to be cut loose from the apron strings at some point! Who's to say that sending kids off to University at the age of 18, when they been wrapped in cotton wool all their lives, makes for well rounded individuals?

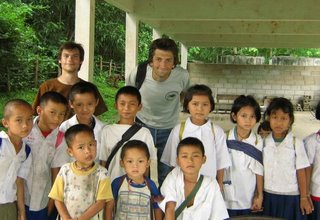

We've been on a home-stay project in the Karen tribe village of Pa Do Tha for the last two weeks organised through this company. The Karen are the largest hill tribe in Thailand, with almost half a million population in Thailand, and 100,000 in Tak province alone. They are sedentary farmers, who employ land rotation rather than the nomadic agriculture of some other tribes. Teaching in this part of Western Thailand, provided me with an opportunity to take a glimpse at how kids get on when they are left to their own devices and what a tribal village is like in terms of justice, liberty, freedom and equality when semi-divorced from the state. Mind you, two weeks ain't a long time, so this is partly conjecture. Read on if you will...

Firstly, I'll say a bit about the environment and community. Each morning I awoke into a world alive with the sound of cockrels crowing, pigs snorting and logs being chopped. I got up, washed in the river or with water from the cold tap and then strolled off to the school to try to teach English for four hours or so. I'd have all my meals made for me by the support staff, and then help out with other tasks such as rebuilding the home stay house and helping sow seeds at the weekend. The house we stayed in to begin with belonged to a local family, but we moved to the proper home stay residence once we'd repaired some superficial problems their (mainly building a fire for cooking). The local houses are built mainly from bamboo, raised from the ground on teak support beams. They have corrugated steel roofs to keep out the rain. Largely open to the elements, there is one contained sleeping room, but the rest is an open veranda. Here we cooked, ate, read, socialised and played guitar badly. Ban Pa Do Tha has about 40 families and as many homes. Apart from the Kings' donation of solar generated electricity and attendant panel generators (which means that they now have electric light and TVs), the only other significant construction in the village is the concrete school house, which was built about 15 years ago. This is was quite large with three classrooms. Perhaps too large, considering that there are only 14 registered pupils making up two classes. One room was empty indefinitely. There is now only one teacher for the whole village, so we came as a useful support to her if we did nothing else. In the neighbouring village of Umphang Kee they have three teachers, so you can see that she had a tough job on her hands. She was happy for us to teach the classes as we liked, but since she spoke no English we were left to our own initiative to work out the standard of children's English, ability in general and what to teach. Initially James taught the younger kids (7-10 years old), and I took the slightly older ones (9-10 years old). After some trouble keeping attention and discipline at certain points of the day, we taught together for just over a week. I'm not sure quite how the teacher coped usually with two classes. Presumably she set work for one, whilst spending contact time with the other. James and I both feared that she may have kept order buy giving children the odd tap with a stick, although we never saw this. Apart from the proper students, there were a number of other children from the village who would wander in and out of the school, usually a bit younger than the rest of the students and a (no doubt unintentional) disruptive influence.

Pa Do Tha is a pretty harmonious place outwardly, and often it seemed idyllic. The questions I was most unsure of cast my mind back to Auroville, and to others areas; how were decisions reached? How did hierarchy penetrate daily life? What was the role of women and the treatment of animals like? What would it be like to be outcast from society? I use the term semi-divorced from the state, but the role that the state does play in the lives of the hill tribes is long established and heavily legislated. According to the book I purchased from the Hill Tribe museum in Chiang Mai, 1959 saw tribe welfare committees set up to deal with four problems of hill tribes as the government saw it. These were: 1. Depletion of natural environment and resources, 2. Opium cultivation (not something which the Karen traditionally practiced) 3. Security problems and 4. low standard of living tribal living. All these seem to be hill tribe problems from a Thai state perspective, rather than the tribes opinion. By 1982 a new national policy on hill tribes focused on administration, opium & addiction and social & economic development at national, regional, provincial and district level. Self help groups and councils exist which give the tribes a level of influence, but the policy seems to be built around integration and eventual assimilation into Thailand from the little I've read. James and I both detected Karen traits in the village only here and there. Had I known nothing about hill tribes, I still suspect that I would have just thought this was a run-of-the-mill Thai village. They raise the Thai flag outside the school each day, and have calendar's with the King's photo in the classrooms.

Supat, our guide, informed us that the village was run by village elders, and decisions were made by a system of one vote per family. I'm not sure how this would work; would it always be the patriarch who decided? The women certainly did very similar manual labour in the fields to the men, and they didn't seem to be precluded from anything while we were there. Farming work, especially the sowing which James and I helped with, was a large communal activity peppered with plenty of chatting, gentle ribbing and singing to relieve tedium during the demanding physical work. Most of the adults seemed very happy, and on their way home they were quick to flash a grin at me or ask how we were enjoying ourselves. Work is everyone's concern and the kids would often be in class one day and pulled out to help on the farm the next. We discovered that following the field burning of April, May is the corn and rice planting month. Generally the families and kids seemed to get on extremely well together. Every evening people would drop in to visit Supat and his mates or to ask James and I for a quick unplanned English lesson. Communal drinking of the local rice moonshine was common as an apertif or just as means to a drunken ends. The kids often shared their food amongst themselves without thinking twice about it. Dogs, chickens and cats all lazed around, living without restriction or much human interference, this was true to a lesser extent of the cattle and water buffalo (although the same couldn't be said of the penned-pigs). One of the oldest men in the village, Too Nduoy Por, took a bit of a shine to me and James and often came round to see us or Supat. He even conducted the Karen 'good luck' ceremony on James' birthday, but more about that in another post. James and I guessed that the only way to deal with major disputes in this environment (if they couldn't be solved by the village council) would be to make damn sure they didn't arise in the first place. You can't escape your neighbours, so you'd better get on with them. There were certainly strong personalities in the village, but none of these equated to a pecking order or instances of bullying as far as I could see. I don't know what it would be like if you were gay, for instance, growing up here. Perhaps it would be accepted, but I suspect you'd just have to pretend you weren't.

James cannily observed perhaps the main difference between the British society we are used to and this life is that everything is extremely informal. If somebody doesn't turn up for a social event (though not work) nobody bats an eyelid. Often people seemed to make arrangements to do something which never happened, but also things occured spontaineously with ease; on a few occasions James and I would find ourselves teaching in the evening when we were just about to turn in for bed.

Next a bit about my teaching experiences. My first day wasn't too bad at all. The first task was to assess the standard of each child's English. Verbal repitition and copying down had been ground into the pupils' heads as the way to learn in the classroom. Similarly their ability to accurately reproduce letters and words was good, and surprisingly neat. This was a major achievement considering it is an entirely new alphabet. They seemed to have a broad knowledge of English basics judging from the random questions I was asking them, but this is where I began to go wrong.

I imagine assumptions about a whole classes ability, just because one or two kids can answer your questions is where a lot of teachers can go wrong. Knowledge is gained in patches, and usually a non-linear fashion: there are often gaps in knowledge somewhere. On my first day I moved off at pace covering basic questions, answers and vocab, whilst the kids relied on their short term memories to repeat what I'd said. I came away from the first day feeling pleased with what I'd managed to get through, but it was a false impression. James had a much tougher first day, teaching the younger children a much more basic level of English, and realising he'd have to teach the alphabet and even basic numbers repeatedly. I felt a bit sorry for him, because I'd sailed through the first day with no problem (I thought).

The following Monday, I got a better taste of what the children were really like and their true personalities. The kids who were starting to get to know me felt that they could try it on a bit, and by the end of the day I had trouble maintaining their collective concentration. Teaching English vocabulary isn't too tough if you can't speak the student's language. Dealing with differences in ability, student boredom through not being stretched and student frustration through taking a big longer than your peers to pick things up, is difficult. Because they learn English in patches (i.e. whenever volunteer teachers are available), they know some basics by heart, but other areas are neglected. For instance it took me four days to realise that Wssoot (one of the children) couldn't count to ten properly. The session where I was teaching the time must have completely excluded him.

Dealing with misbehaving children, is a skill and it requires a bit of psychology. I think you have to avoid being dragged into an obstinate battle of wills, which ends in a fruitless stalemate. I started to see the tip of the iceberg my Dad has had to deal with over the last forty years teaching in Paddington: Dad, you're better man than I. I must also mention that the school day - two session of two hours - was simply too long to expect young children to concentrate for. We were not in a position to start challenging how the school was organised, though.

By the first Tuesday, I'd realised that focusing on understanding individual words, rather than complete sentences was exculding too many of the class who simply didn't follow my meaning. I wasn't at liberty to break up the group, and I wouldn't have been able to predict the consequences of doing so (i.e. damaging certain children's confidence). A bit of Morton prevarication followed... eventually, I decided to go back to complete questions, answers and vocab. I drew up my own little syllabus of the following: colours, food, sports, weather, directions, body parts and clothes. After that I tried to teach them the meaning of basic words: I, you, me, his, her, this, that etc. That was as complex as I could make it, but the speed of some children in picking things up far exceeded my expectations. Sticking to small area with lots of recapping started to work. The pupils were able to guess the answers without prompting and starting grinning. When the kids were engaged, I enjoyed it a great deal too.

On Tuesday afternoon (3 days in) some of the children really started to play up during the final hour. They were hitting each other, bouncing up and down on the back bench, flicking elastic bands around and miming urinating. In short, they were doing all the stuff my mates used to do at school. When one of the bands hit me, I decided that enough was enough. I'd have to do a very short detention session for a couple of the kids at the end of the day. In retrospect I don't know if this was a good idea or not in the battle to win the children's attention. The teacher had gone off to a meeting and James was working with the other class so I was left to my own devices. I felt I couldn't let Wssoot and Sonchai go without a (very mild) rebuke of this kind. They got the idea of why they were being detained, but were still pissing around when I let them go 15 minutes after the others. Of course, this meant that they were less co-operative the next day, and witheld some of their knowledge deliberately. C'est la vie: they'd forgotten about punishing me by the afternoon.

I kept in mind that the tiny class size I had - 7 - would be a dream for any qualified teacher, so I didn't have much cause for complaint. Things got easier for the rest of time at Pa Do Tha, because the other teacher returned, and James and I paired up to teach one class at a time. This made discipline better, and gave the kids more variety of styles. When the kids muck about and are genuinely funny it's very difficult to stop yourself from laughing. For example, when I was teaching the weather and moved onto lightning, Wssoot mimed being struck by a bolt and falling down prostrate on the floor with his tongue lolling out. I could help laughing out loud. Another time, whilst I was writing on the board, James kept an eye on the class. Spotting James looking a bit bored, Sonchai got up from the desk, waltzed over to the window, gobbed out of it with all his might, turned round, saluted James and marched back to his desk. James just laughed his head off at his temerity instead of telling him off. This did mean that we got the kids 'onside' to use James' lingo, but we didn't set the best example.

As we spent more time with the elder class, we realised how large the variation of ability was and learnt how to keep the children occupied. The children are taught to believe that repitition and copying down are the work. If they aren't doing either of these, they feel at liberty to amuse themselves. Whilst these two methods are useful, I think they are aren't enough alone. The problem is, trying other methods like group work invariably meant that you came unstuck, because at least one or two of the kids were left to their devices whilst off the teacher's radar. Instead, James and I tried to introduce a splash of colour by getting the children to write on the board and using flash cards. These proved much better, and introduced an element of competition among the kids. After finishing a solid week with the elder class, I think they'd picked a solid chunk of the vocabulary.

By the end of our stay we definitely had a good taste of what teaching is like, but I wonder how much the children gained during that time. Perhaps only a small chunk. The only negative experience we had, was when teaching the younger class on the last three days. One child, Sugaiya, was withdrawn and looky teary for the whole of the morning session. Clearly there was something fairly major upsetting her. We were concerned about her, but of course we couldn't communicate with her to see what was wrong. I was tempted to call the teacher in to check on her, but James said it was best to leave it. As the day progressed and the girl didn't cheer up or start to work, the other kids started giving her some stick which we cut out immediately. When the teacher did pop in, James was proved right. She walked up to the little girl and tapped her on the head with pen and told her to pay attention rather than asking her what the matter was. This was a long way from how James or I would have handled the situation.

James and I were genuinely sad to leave the kids at the end of the week, no doubt the same as teachers before us. The kids were sparky and genuinely friendly. They tended to look after each other, and school yard spats were not carried back home, where we often saw all the kids playing together. They were capable children and likely more level-headed than their English peers. Above all they all seemed very happy and generally confident to be themselves.

The other thing I was keeping my eyes open for in Pa Do Tha was the sustainability of the village. Particularly I wondered what lessons could be learnt that could be applied at home. The emphasis was very much on using local produce and materials. The homes were bamboo, the bath was the river, the food largely produced in surrounding fields, forests & fields and plastic bottles/other waste materials were re-used (superior to recycling). Rightly or wrongly, the close relationship between man and animals is heavily developed. Pets don't exist as such. Dogs catch vermin or work in the fields. Cattle and Water Buffalo provide food and income. Elephants are a form of transport, aource of heavy labour and tourist revenue. Less sentimentality, as I noticed in India, may often mean more respect for animals. A popular form of transport to get from Pa Do Tha to Umphang in one direction, or Umphang Kee in the other direction was by low powered motorbikes, which most of the younger people owned or had access to. These were suited to the windy, steep and sometimes partly flooded dirt tracks which joined the villages. Whilst not exactly sustainable, the fuel consumption of these is far better than a car. The petrol was sold from vending machings that looked much like soft drink dispensers in most roadside stores. There were also a number of push-bikes and the odd SUV, but encouragingly the main way to get around in Pa Do Tha is still by foot. The solar panel generated electicity had only been available for one year, but already it had started to influence life here, with people buying televisions, VCD's and stereos. Supat remarked that people were often unfit for work in the fields of a morning now, as they stayed up too late watching movies or listening to music.

By the end of the fortnight, James and I were pleased to return to Bangkok. We wanted to wash our clothes thoroughly, have control over our own meal times and escape the mosquitos. It's no surprise that most westerners easily welcome back their creature comforts when losing them for a short time. What will stay with me about this trip however, was how quickly me and James adapted to a different lifestyle, and how little human beings need to get by (provided they have a fertile environment around them). As natural resources dwindle and our present technology dependent lifestyles come under threat, who is to say that humankind won't have to readjust to a society similar to this one? On the other hand, if technology and cultural assimilation continue to penetrate every nook, life as it exists in the village today could become a token element of the Karen tribe or even be wiped off the map altogether. What an enlightening two weeks! Time for me to do some more research!

Loh Dalum bay on the Isthmus at Ko Phi Phi. The trees behind the deck chairs bear the damage of the 18ft tsunami wave.

Loh Dalum bay on the Isthmus at Ko Phi Phi. The trees behind the deck chairs bear the damage of the 18ft tsunami wave. Sandbags left over from the initial stages of the tsunami recovery operation. These are strewn over 'prime real estate'.

Sandbags left over from the initial stages of the tsunami recovery operation. These are strewn over 'prime real estate'. Rebuilding on the main drag at Ton Sai.

Rebuilding on the main drag at Ton Sai. Temporary huts remain home for some people on Phi Phi.

Temporary huts remain home for some people on Phi Phi. That's quite nice. Nr. Mahya Bay, Ko Phi Phi Leh.

That's quite nice. Nr. Mahya Bay, Ko Phi Phi Leh. Clear and clean water of Ko Phi Phi.

Clear and clean water of Ko Phi Phi.  Superman returns. Mahya Bay, Ko Phi Phi Leh.

Superman returns. Mahya Bay, Ko Phi Phi Leh. Limestone ridge, Ko Phi Phi Leh.

Limestone ridge, Ko Phi Phi Leh. As flat as a mill pond. A serene evening journey from the mainland to Ko Pha Ngan.

As flat as a mill pond. A serene evening journey from the mainland to Ko Pha Ngan.  Cheer up! Hendrix would have appreciated the boat ride.

Cheer up! Hendrix would have appreciated the boat ride.  Asphalt turns to dust. A preminition courtesy of the road to Tong Nai Pan Yai beach, Ko Pha Ngan.

Asphalt turns to dust. A preminition courtesy of the road to Tong Nai Pan Yai beach, Ko Pha Ngan.