28th November 2006, Day 253

28th November 2006, Day 253Arequipa, Peru

I'm a bit ill today. This is the first time I've felt off colour since I was in India back in March/April, so I'm not doing too badly really. We arrived in Arequipa - the white city, constructed from white sillar stone - yesterday after another of the over night bus rides you'd really rather avoid. Arequipa is 2,300 metres above sea level and that's the sort of height where altitude sickness kicks in. After feeling tired all day we cooked some spaghetti in our hostel's dodgy kitchen. A night of many trips to the toilet and an aching stomach followed. I was then woken up at midday by someone rattling the bedroom door violently. When I went to find out just what was going on, I realised that the ground was shaking due to a small tremor. Very foreign!

Nazca, which we've just left for Arequipa, is the most noteworthy place I've been to in Peru so far. Many people are familiar with the Nazca Lines - large land drawings or geoglyphs which can only be appreciated from the air. In fact the geoglyphs cover over 200 square miles. The purpose of these lines has been the subject of much debate and wonder. The huge figures include a monkey, a hummingbird, a spider, a condor, a dog etc. Sadly before the lines were rediscovered by Dr. Paul Kosok in 1939, the Peruvian stretch of the Pan American highway had already been built right through part of the lines. You can see a photo of the road next to the geoglyphs of James' latest blog entry. Despite many years of research since the lines were rediscovered, no scientific conclusion has been reached as to why the lines were built in the first place. The main theories are thus:

1. Maria Reiche. The first major researcher (her archeological partner Dr. Paul Kosok stopped work on the lines in 1948) and one of the most respected, Maria believed that the lines were primarily an astronomical calendar, with geoglyphs for summer (the Hummingbird) and winter (the Condor) equinox. The geoglyphs calibrated the year into a calendar and made sense of the heavens by tracking their movement - a unique observatory.

2. David Johnson. David is still conducting research but believes that the lines referred to where subterranean water could be found in this arid location - in other words the Nazca lines are a giant water map. The large pointing arrows supposedly indicate under ground sources of water.

3. Robin Edgar. Robin theorised that the Lines were a response to an unusal period of solar eclipses that took place around the time when the Nazca Lines are suspected to have been constructed. The geoglyphs were to be seen by a giant 'Eye in the Sky' - which is the way that the sun and moon might have appeared to the Ancient Nascas during a total eclipse.

4. Jim Woodman. This theory is based around the feeling that something as large as the Nazca Lines could only have been produced for an aircraft's perspective. Woodman managed to construct a hot air balloon from materials and techniques available at the time, to add strength to his argument.

5. Erich von Däniken. Erich believed that the lines were created as runways for Alien spacecraft. I think this is a cracking idea.

This photo of the monkey geoglyph was taken by the Peruvian airforce photographic service on behalf of Maria Reiche. In the late afternoon of our first day in Nazca, I had the good fortune to stumble across Viktoria Nikitzki, who runs the Maria Reiche centre which is also her home. We were looking for the centre - mentioned in the Lonely Planet - and had no idea who the busybody was staring us down outside a dusty brick building. 'Is that your washing? I can help you with that... if you are here for my lecture.' We were indeed looking to kill two birds with one stone, so she called out to one of her nieghbours cycling past and soon our dirty linen had been taken in by some bemused local women, who blinked in uncertainty at two sunburnt gringos. Aside from getting our washing done, Viktoria turned out to be one of the most mysterious and compelling people I've ever met. She was a personal friend and disciple of Maria Reiche. We agreed to meet her later for the lecture, and went back to our poorly ventilated and hence smelly hostel. I'll name and shame the place actually - Alegria II - the sheets were dirty and I would compare the smell of our room to vinegar mixed with dirty socks. Foul.

This photo of the monkey geoglyph was taken by the Peruvian airforce photographic service on behalf of Maria Reiche. In the late afternoon of our first day in Nazca, I had the good fortune to stumble across Viktoria Nikitzki, who runs the Maria Reiche centre which is also her home. We were looking for the centre - mentioned in the Lonely Planet - and had no idea who the busybody was staring us down outside a dusty brick building. 'Is that your washing? I can help you with that... if you are here for my lecture.' We were indeed looking to kill two birds with one stone, so she called out to one of her nieghbours cycling past and soon our dirty linen had been taken in by some bemused local women, who blinked in uncertainty at two sunburnt gringos. Aside from getting our washing done, Viktoria turned out to be one of the most mysterious and compelling people I've ever met. She was a personal friend and disciple of Maria Reiche. We agreed to meet her later for the lecture, and went back to our poorly ventilated and hence smelly hostel. I'll name and shame the place actually - Alegria II - the sheets were dirty and I would compare the smell of our room to vinegar mixed with dirty socks. Foul.We returned to Victioria's spartan home at seven o'clock for the evening lecture, by which point it was dark. We stumbled through a dimly lit and ramshackle anteroom into her 'lecture theatre', the largest room in the house with a mud floor and single lamp to light a scale model of the Nazca Valley. This came in to view gradually as the light warmed up. Barely had James and I settled down on the stone bench before Viktoria rejoined us. Unprovoked, she doled out what I would call 'a piece of her mind' to James and I. I didn't mind, however. I received the impression that she would just have easily have shared the same information with a three year old or a mafia stooge pointing a gun at her head. To put it simply she didn't give a toss. Being a bit of a wimp myself I always admire this attitude in people. We talked a little at the beginning about South American politics whilst we waited for some other customers who ultimately never showed up: she praised Chavez and Morales, but employed a grave tone to describe the former's relationship with Castro. She declared Cuba to be the only Latin American country with a monarchy! Aside from that, all bitterness was directed against Bush, and his attempts to unsettle the fledgling neo-socialist movement spreading across the continent. Her speech was littered with frowns, knowing looks, pregnant pauses and grins. She had a well-turned 'woe is me' element to her character which she brought up now and again to her advantage. She was deliberately comedic, then suddenly serious as she talked about her effort to 'save' the lines without the tools to do it. She painted a picture of herself surrounded by unscrupulous bureaucrats and nincompoops. Maybe it was true.

You could describe Nikitzki as 'weird' I suppose. James had a number of intelligent questions to ask about the lines that she simply didn't answer because it wrested the perogative away from herself. I'm not doing the best job of making her sound charming, but she was to me (although I sympathised with James, who still valued the experience). Clearly European by origin, I asked Viktoria where she was from - 'I am from cosmos' she replied. I suspected that she might have been German like her friend Maria Rieche, but James reckoned she was French on the basis of her gesticulations. She went on to talk about her neighbours, one of whom sells Coke on the street side, while her teenage daughter goes to discos (she will be pregnant within the year according to Viktoria - she's sounds like a conservative politican from 1991 now doesn't she?). She scruched up her face. Within Viktoria's 'cosmos' Coca-Cola does not exist.

A brief digression. Around here Coke is delivered in tank like vehicles and they sponsor the street signs. There's not much competition in Peru, everything in the supermarket seems to be made by a few companies - mainly Coke, Nestle or Unilever.

A brief digression. Around here Coke is delivered in tank like vehicles and they sponsor the street signs. There's not much competition in Peru, everything in the supermarket seems to be made by a few companies - mainly Coke, Nestle or Unilever.The local 'Inca Kola' used to have much bigger share of the soft drinks market in Peru than Coca-Cola, so they bought them out. The same happened in India with a cola drink called 'Thums Up'.

Coke make a big deal of the fact they are franchised on a country by country basis supporting local economies. So they're not a multinational at all, see? Why do they have a CEO and international board of directors then?Enough of my pet obsessions.

Back to the Maria Reiche centre. To elaborate on my earlier point, the mian thing Viktoria lamented about Peru was the endemic corruption and the poor education which has hatched an aquiescent attitude among the poor (which is the overwhelming majority of the population). She described a hypothetical situation in which an official might spit upon a local: 'hmm, perhaps the wind blew the wrong way' would be the response of the average Peruvian, she thought. She'd recently heard (we think incorrectly) that there was an attempted coup against Morales in Bolivia and she was upset that there was no one in Nazca to discuss it with. Her dignity refuses to allow her to leave Nazca. Having met her I felt she was isolated and I pitied her a little, which she would have hated.

OK... so what about the Nazca Lines? That was the point of the lecture, wasn't it? We did get onto them eventually. Gratitude. That summed up what the lines were about according to Viktoria (she was doing a good job of talking from her own perspective not Maria Reiche's, but this was clear with a bit of research). In what way were the Lines about gratitude?

The lines were built by Ancient Nazca civilisation (300bc-800ad) from which the site now take it's name. According to Maria Reiche, who studied the lines for 50 years, they an elaborate astronomical calendar created to mark risings and settings of the sun, moon and stars. This is outlined in her publication 'Mystery on the Desert' (first published in 1949). The crux of Reiche's work was based around where the sun's rays fell during sunrise at Summer and Winter equinox. The Hummingbird (which is associated with the warm summer months) was built at the point the sunlight reached at summertime and the Condor with it's huge beak the winter solstice. This was also a place for ceremonies to celebrate life and give thanks for it.

We moved onto hydrology. I may be wrong, but it seemed Viktoria again mixed her own opinion with that of Reiche; at least so far as we can tell in Reiche's book. Viktoria talked about water - large triangular pointers were 'drawn' to signify locations of subterrean water ways (also proposed by Johnson). Viktoria produced some divining rods and two bottles of water, at this point - one full the other half full. After waving some rods around a bit she demonstrated the art of divining... if you were prepared to use your imagination a bit.

I hope I am not being too facetious about Viktoria; really the bulk of her work is pretty serious, and I am not trying to make light of that. Quirks and foibles are what gives a personality colour, which is why I mention them. I truly admired her, even if I did take a little of what she said with a pinch of salt.

A wonder of the world (though not in any official sense), the huge geoglyphs probably won't be around for decades to come. Viktoria is negative about the future of the lines. She is convinced they are being destroyed. In recent years the inhabitants of Nazca have been dumping their rubbish, (plus that left by tourists) on the pampa or plains. How long before it becomes a huge mountain the eats up the 'glyphs? More importantly, as Maria Reiche pointed out as long ago as 1976, the area, which was previously almost rain free, has been receiving increased precipitation year on year for long time. In Viktoria's words:

"There has been deforestation everywhere so water from the highlands comes down to the Lines in streams and rivers. The Lines themselves are superficial, they are only 10 to 30cm deep and could be washed away. There is no maintenance or any sort of care for the Lines. Also there is threat by the weather. Nazca has only ever received a small amount of rain. But now there are great changes to the weather all over the world. The Lines cannot resist heavy rain without being damaged."

The Nazca Lines are supposed to be a UNESCO world heritage site, which means they should receive some form of funding to help preserve them in the long term. Viktoria is adamant that no work is being done to protect the lines, and thinks that UNESCO is a load of nonsense. She reckons whatever money might be received for the protection of the lines goes straight into the pockets of Peruvian politicians, civil servants or officials. The Maria Reiche Centre is calling for international intervention to protect the geoglyphs, and wants local pollution controls and irrigation systems to divert water away from them. Viktoria doesn't think they'll listen to her, despite endless letters and overtures to government departments, archaeological and environmental groups.

Before we left her for the evening, Viktoria intentionally sent us on a guilt trip about wandering away from her lecture without doing anything to support the cause of the Lines. The following day I returned to Viktoria's house to help cut down what she called 'the Espinola tree' in her backyard (NB: removing the tree and preserving the lines may not be directly related). Armed with a vicious machete I set about this task whilst trying to avoid her pet turkey and kittens with the falling foliage. 'No! Too big, you must chop it up and throw over the back wall' were Viktoria's barked instructions when I lopped off the first large branch. I spent three hours being scratched by large thorns and balancing precariously on a crumbling brick walls, so this was a bit of a fool's errand. The thing is, I do take the odd measured risk, and this was not comparable to an Evil Kneivel stunt. I just wanted to put Viktoria's mind at rest as she continually referred to some (possibly exaggerated) security threat - she thought people could climb into her sealed yard via the low hanging branches. Anyway, I laboured away for a while with the help of another German volunteer and got rid of the best part of the tree. 'My cat will be waiting for you when you get down if you drop a branch on him', said Viktoria with a toothy grin which reminded me of Mark E. Smith.

James turned up fresh from his flight to help for the last half an hour or so, and Viktoria was grateful for the work. We were rewarded with some jam she made from the pods of the tree I was chopping down.

In the afternoon, after I washed off four years of dust from 'the Espinola tree' and went for a more affordable tour of Nazca than the flights. My guide Jan (short for Janssen not Juan), was a trained archaeologist and a very pleasant guy to boot. He was about my age and we got on very well. Before we set off, I tried to verify some of the general points Viktoria had made with Jan. He agreed that there were huge problems with corruption, but thought that the situation was a little more complex than Viktoria suggested - particularly education on historical sites in Peru for Peruvian nationals. He had a distinct personality to Viktoria; I asked him what his pet theory on the Nazca lines was and he said 'nothing is believed until proven in archeology.' I was going to receive a very different perspective.

Before we started the tour I wanted to find out a little about Jan and he appreciated the opportunity to take his tourist guide hat off for a moment. Jan talked a little about the basketball coaching he did on Saturdays for a couple of hours in a poor village near Nazca. He wasn't too downbeat about the country's future and talked about his wife and child and his ambition to get back into archeology and work in Egypt. He also talked about how much he loved the Rolling Stones and the rock band he was in himself. When 'I'm Free' hollered by a young Jagger came on the radio in van on the way back, I thought he was going to punch the window in joy.

Our first stop was at the aqueducts, built by the ancient Nazcas (300bc-800ad). I am not totally certain but I believe these were built to preserve and improve access to natural waterways. Channels were cut down into the turf at the point which the water was closest to the surface. They were an amazing feat of engineering. Reeds which grew up from the large stone banked channels, blocking the passage of the water were cut away each year by the Nazca population, with individuals travelling down inside the meadering and fractured subterranean channels. It was a job which was delicate and very dangerous. Very few of the orginal aqueducts have been repaired or altered and they are still used today. A mark of the quality of the water is the numerous little fish which you can see swimming in the channels. Spiral walkways were built down to some of the openings for carrying large water containers down to the water and back up with ease (some wells were as deep as 20 metres).

Next we travelled on to some of the outlying geoglyphs; places not covered by UNESCO status. Jan talked for a while about the established uses of the Lines of which there is really just one. They were definitely used in ceremonial rituals of one kind or another, their other purposes are open to theory. This has been established via a myraid of fine ceramic found in all the geoglyphs. Jan was more concerned about the plight of these geoglyphs and the rubbish dumping I mentioned before, than what is happening to the better known lines which the plane tours cover each day.

One surprising thing is the limited industry in the area. Jan showed me some of the iron and aluminium ore which is abundant here. Also present is copper, silver and even gold. Indeed there is one gold mine owned by Canadians heading towards Cusco, and Peru is major player in extracting some of these metals. Frankly I'm amazed, however, that this area isn't off limits having been sold to hard rock mining companies. I understand that hard rock mining is nowhere near as easy and profitable as mining for fossil fuels, but if we are talking about copper (because of the components of modern electronic devices) and gold, well, that's a different and more profitable matter.

Now we step forward dramtically in time. At our final stop we looked at some of the much later Inca Empire's (1197ad-1533ad) construction in the area. Las Ruinas de Paredones, are the remains of an Incan fort built around 1412 from which the head 'Inca' who ruled the whole settlement could view the whole Nasca valley. It was quite a vantage point.

I was charged a fee of ten soles to visit all the places Jan took me, but evidence showed the behaviour of some tourists who visited these places was poor. The site with it's crumbling bricks were not supported or off-limits to tourists at any point. Peru always has a major battle on it's hands because earthquakes frequently destroy relics of it's rich historical past. Indeed that's the main reason Los Paredones looks the way it does today. That doesn't excuse people walking along the walls, scratching their names in the mud brick or leaving their rubbish in the site itself. 'At least people don't play games of football here any longer', sighed Jan. He made a big point that most destruction of important geological sites in Peru was caused by national rather than international tourism. Whilst we looked at the mud bricks I saw plenty of western names scratched into the former walls, though.

As we headed back into Nazca itself Jan invited me to watch him play basketball that evening and I gladly agreed. I don't know much about Peruvian basketball, needless to say! Sadly James and I had to skip town that night, as the only buses to Arequipa were at night and we didn't fancy kicking our heels in Nazca for another day. When I went to meet Jan to offer my apologies he turned up happy and smiling with his wife and small child. He accepted my excuses with good grace, but I felt like a right idiot.

A few more pictures. The aqueducts built around Nazca by the Ancient Nascas have been well preserved and as you see, are still in use today! Jan chatted to these local guys who were knocking around on Saturday afternoon eating Mango Verde with salt. They knew what I was getting at when I stuck my tongue out in revolt. In fact I thought we were establishing some level of rapport when Jan indicated it was time for the geoglyphs.

A few more pictures. The aqueducts built around Nazca by the Ancient Nascas have been well preserved and as you see, are still in use today! Jan chatted to these local guys who were knocking around on Saturday afternoon eating Mango Verde with salt. They knew what I was getting at when I stuck my tongue out in revolt. In fact I thought we were establishing some level of rapport when Jan indicated it was time for the geoglyphs.Other things we've done in Peru...

Our first port of call after Lima was Pisco (famous for it's grape of the same name). Just below Pisco lies the Parracas peninsula from where you can catch a boat to it's primary tourist attraction, the Islas Ballestas. These isles shelter a veritable feast of wildlife, with Pelicans, Emperor Penguins, Pelicans, Boobies and Sealions. We got some great snaps.

Our first port of call after Lima was Pisco (famous for it's grape of the same name). Just below Pisco lies the Parracas peninsula from where you can catch a boat to it's primary tourist attraction, the Islas Ballestas. These isles shelter a veritable feast of wildlife, with Pelicans, Emperor Penguins, Pelicans, Boobies and Sealions. We got some great snaps. Emperor Penguins on Islas Ballestas. One of the most surprising things about the islands was how intermingled all the different bird species were, boobies, penguins, pelicans and cormorants all stood side by side, apparently not bothering one another.

Emperor Penguins on Islas Ballestas. One of the most surprising things about the islands was how intermingled all the different bird species were, boobies, penguins, pelicans and cormorants all stood side by side, apparently not bothering one another. This is Huacachina, a desert town (which exists for tourists) built around an oasis. We stopped here for the sandboarding that we read about in our Lonely Planet. This involved travelling in a the kind of sand-dune buggy they warn you not to get in on the Foreign and Commonwealth office website. Hey, it had roll cage! The actual boarding (very similar in principle to snowboarding) was not easy. We had several opportunities to throw ourselves off dangerously steep banks, with next to no guidance and no skiing or snowboarding experience necessary. There's a great shot of me rolling down the dune with my bottom hanging out. With much charity James didn't publish it on his blog.

This is Huacachina, a desert town (which exists for tourists) built around an oasis. We stopped here for the sandboarding that we read about in our Lonely Planet. This involved travelling in a the kind of sand-dune buggy they warn you not to get in on the Foreign and Commonwealth office website. Hey, it had roll cage! The actual boarding (very similar in principle to snowboarding) was not easy. We had several opportunities to throw ourselves off dangerously steep banks, with next to no guidance and no skiing or snowboarding experience necessary. There's a great shot of me rolling down the dune with my bottom hanging out. With much charity James didn't publish it on his blog.

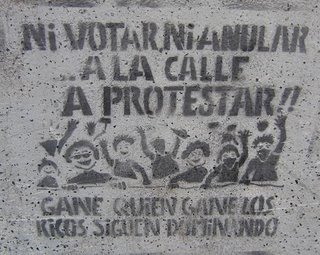

'legislation has been passed regarding scholarships for the PSU(university entry exam), it is now free for the poorest half. The reduced bus fare for school kids now runs 24 hours.' Criminal charges against individual student leaders were dropped. My friend points out this may have been to prevent a student backlash. Some of these Assembly leaders were extremely young, such as María Jesús Sanhueza, an outspoken 16 year old Communist.

'legislation has been passed regarding scholarships for the PSU(university entry exam), it is now free for the poorest half. The reduced bus fare for school kids now runs 24 hours.' Criminal charges against individual student leaders were dropped. My friend points out this may have been to prevent a student backlash. Some of these Assembly leaders were extremely young, such as María Jesús Sanhueza, an outspoken 16 year old Communist.