skip to main |

skip to sidebar

22nd December 2006, Day 278

22nd December 2006, Day 278

Qosco, Peru

A nice break for you all. This will be a quick painless affair with hardly any preaching and just pretty photos. Undo a notch of your post-Christmas lunch belt and relax. For a more detailed post check out James' blog.

We finished the Inca Trail a few days ago. I am bored of talking about it with people in our hostel, so I'll just mention a few things that stick in my mind.Here's Machu Picchu itself, one's reward after a four day hike. It is another of these UNESCO world heritage sites. The UN apparently take bit more interest in this than the Nasca Lines and warn the Peruvian government that even the present regulated tourism here is having a seriously denuding effect. In fact some scientists at the University of Kyoto reckon that the whole city site is slipping down the mountain at a significant rate each year. I'm glad I went because if it might not be here for much longer. When we arrived the city was totally encircled by cloud, but thankfully this passed off and we received our long awaited 'oooh' factor.

The favourite theory for Machu Picchu's purpose was that in addition to it's status as a holy place, it was an outlying retreat for the Inca and his Quechuan nobles in event of an enforced evacuation of Cusco, the capital of Quechuan empire. As it turned out an evacuation was what they had to make after losing battles to the invading Spaniards, fortunately they had a place to go to and plenty of ways to get there. The so called 'Inca Trail', is actually one of a number of different tracks which lead to Machu Picchu, one of the only Quechuan outposts which was never discovered by the Spanish due to a campaign of disguising and hiding it with twigs. Eventually the Inca and his nobles were found and slaughtered but Machu Picchu remained unknown to the Spanish. Nice story, except the vast majority of surviving Quechuans got enslaved. It is an amazing sight, but it shouldn't be forgetten that this is a relic of feudal society. It is a bit like the Peruvian equivalent of visiting Windsor Castle, except that Windsor Castle is much older (!), and that Machu Picchu is a touch more impressive to behold. There's no real reason to commend one more than the other in terms of what they stand for, but there is in terms of how they were constructed. Whilst building the round tower couldn't have been a piece of cake, lugging huge chunks of stone up seemingly vertical mountains to build earthquake proof walls without the use of track animals must have been tougher.To me, the four day hike was a mixture of exertion, surprise, anti-climax, guilt and wonder. You pass plenty of other Quechuan ruins on the way to Machu Picchu which were basically stop off points or decoys for Machu Picchu itself: Llatapata, Runkuraqay, Sayacmarca, Phuyupatamarca, Intipata, Winaywayna and Intipunku! It's a long walk in total, includingg three high passes but if the rain stays off you're alright.  This is the Urubamba river which flows through the sacred valley. The view is from Sayacmarca ruins a sentry point. I provide this level of detail so I can refer back to it in a year, not because you want to know. You can see how dramatic the Urubamba valley is from this picture. In Agua Calientes (Machu Picchu pueblo), which lies at the bottom of the mountains and the entry point to Machu Picchu you really get an view of how uniquely sheer these mountains are, as they shoot off into the cloud and out of sight. Pretty.

This is the Urubamba river which flows through the sacred valley. The view is from Sayacmarca ruins a sentry point. I provide this level of detail so I can refer back to it in a year, not because you want to know. You can see how dramatic the Urubamba valley is from this picture. In Agua Calientes (Machu Picchu pueblo), which lies at the bottom of the mountains and the entry point to Machu Picchu you really get an view of how uniquely sheer these mountains are, as they shoot off into the cloud and out of sight. Pretty.

Some of 22 Quechuan porters playing a version of the game 'Sapo' at the Chakiqocha campsite, during a break we had to encourage them to take. One of the good things about using GAP adventures is that they pay the porters a reasonable wage and employ porters up to the age of 63 without shoving them on the scrap heap. At our first campsite (Yunkachimpa) each member of the tour group and each porter introduced themselves and said a few words which went a long way to humanising the group. I gave them a 'long live Quechuan culture' fisted salute. It was met with indifference. Percy, our group leader (he told me to ask his Dad why he named him Percival), told us a couple of very interesting things about the porters. Percy himself is half Quechuan. Firstly most of the porters have never strayed much beyond the city of Cusco, much less outside the department of Cusco. Percy himself, who I imagine is better more 'wordly' than many of the porters had never seen the ocean until five years ago and he is 31 now. Secondly there is a great deal of stigma about being Quechuan and some of the porters will deliberately speak in Spanish in an attempt to side step this. To put this in context it's been nearly 500 years since the Spanish invaded.So why do you need the porters? The porters carry all the food, tents, sleeping bags, gas cannisters and water proof mats you need to camp. They run the length of the day's trail before you so they are set up by the time you arrive. They cook all your food and wash up all your dishes. They create drainage ditches around the edges of your tent for when it rains. They wake you with hot water to wash your hands and a drink in the morning. Basically they do everything but wipe your arse. I hope our eventual tip was generous. Supposedly their options for farming locally aren't great because of small land holdings in certain villages.

Some of 22 Quechuan porters playing a version of the game 'Sapo' at the Chakiqocha campsite, during a break we had to encourage them to take. One of the good things about using GAP adventures is that they pay the porters a reasonable wage and employ porters up to the age of 63 without shoving them on the scrap heap. At our first campsite (Yunkachimpa) each member of the tour group and each porter introduced themselves and said a few words which went a long way to humanising the group. I gave them a 'long live Quechuan culture' fisted salute. It was met with indifference. Percy, our group leader (he told me to ask his Dad why he named him Percival), told us a couple of very interesting things about the porters. Percy himself is half Quechuan. Firstly most of the porters have never strayed much beyond the city of Cusco, much less outside the department of Cusco. Percy himself, who I imagine is better more 'wordly' than many of the porters had never seen the ocean until five years ago and he is 31 now. Secondly there is a great deal of stigma about being Quechuan and some of the porters will deliberately speak in Spanish in an attempt to side step this. To put this in context it's been nearly 500 years since the Spanish invaded.So why do you need the porters? The porters carry all the food, tents, sleeping bags, gas cannisters and water proof mats you need to camp. They run the length of the day's trail before you so they are set up by the time you arrive. They cook all your food and wash up all your dishes. They create drainage ditches around the edges of your tent for when it rains. They wake you with hot water to wash your hands and a drink in the morning. Basically they do everything but wipe your arse. I hope our eventual tip was generous. Supposedly their options for farming locally aren't great because of small land holdings in certain villages. This IS the Inca Trail. Some of it uncovered post Hiram Bingham's 'rediscovery' in 1911, some of it rebuilt. The local Quechuan farmers who lead him to Machu Picchu had always known about it. When the trails were orginally built it they had channels along which water ran built along their entire length. This maintained the tiring Quechuans. Very few parts of the four day trek route have this feature today.I still find it hard to believe that Percy managed to do the entire four day hike in eight and a half hours on one occasion!

This IS the Inca Trail. Some of it uncovered post Hiram Bingham's 'rediscovery' in 1911, some of it rebuilt. The local Quechuan farmers who lead him to Machu Picchu had always known about it. When the trails were orginally built it they had channels along which water ran built along their entire length. This maintained the tiring Quechuans. Very few parts of the four day trek route have this feature today.I still find it hard to believe that Percy managed to do the entire four day hike in eight and a half hours on one occasion! View of the snopwcapped Andes from the Chakiqocha campsite at the end of day two. I'm not sure I'll see anything like this again. 'Day two is the hardest' is most people's assessment of the trail. It is true that Dead Woman Pass in the morning is a challenge, but I would say most people, as long as they aren't truely unfit, could manage it. One woman in our party had two false hips.

View of the snopwcapped Andes from the Chakiqocha campsite at the end of day two. I'm not sure I'll see anything like this again. 'Day two is the hardest' is most people's assessment of the trail. It is true that Dead Woman Pass in the morning is a challenge, but I would say most people, as long as they aren't truely unfit, could manage it. One woman in our party had two false hips. All the tour parties gathered at the Sun Gate. Ha ha! Losers! This is what should be known as the Cloud Gate, supposedly the best vantage point for your first view of Machupicchu. Actually I ran to be the first one here, there was nothing to see but whispy whiteness. Incidentaly I was first one to climb to climb Dead Woman Pass and Runkuraqay High Pass too. Except for the porters.

All the tour parties gathered at the Sun Gate. Ha ha! Losers! This is what should be known as the Cloud Gate, supposedly the best vantage point for your first view of Machupicchu. Actually I ran to be the first one here, there was nothing to see but whispy whiteness. Incidentaly I was first one to climb to climb Dead Woman Pass and Runkuraqay High Pass too. Except for the porters.

This is me at the top of Waynapicchu, the mountain overlooking Machu Picchu which you can see in the photo at the top. I'm glad I went travelling, 'cos it means I can do this sort of stuff. Back to your Turkey sandwiches, or Guinea Pig if you're Quechuan. I'll be having a picnic in the sun somewhere.

This is me at the top of Waynapicchu, the mountain overlooking Machu Picchu which you can see in the photo at the top. I'm glad I went travelling, 'cos it means I can do this sort of stuff. Back to your Turkey sandwiches, or Guinea Pig if you're Quechuan. I'll be having a picnic in the sun somewhere.

10th December 2006, Day 265

10th December 2006, Day 265

Qosco, Peru

At the beginning of this week, the future of South America was at a cross road of sorts. Since Hugo Chávez was elected in 1998 he has been promising a second Bolivarian revolution in South America. To complete this goal he faced a tough general election, which would make or break the leftist movement he inspired together with his vision of a new South American unity.

The photo to the left is detail from a mural in Qosco (the Quechuan name for Cusco) and it represents something which arguably Bolivarianism or more specifically Chavismo is aiming to put right. The Spanish conquests of the 16th century, spelled disaster for the indigenous American civilisations. After losing long battles against the invaders, native American people were decimated by murder, enslavement and non-native diseases accompanying the conquistadors. It spread like a epedemic from the pockets at which the invaders arrived and pushed inland. Estimates vary widely but some indigenous groups suggest that as many as 200 million native people were reduced in number to 12 million. Of those who did survive as slaves to work the land for precious metals, they lived a half-life as an intolerably hard life and new religion was forced upon them. As so many indigenous Amercians slaves died they had to be supplemented with slaves from Africa, who existed in the same state of misery. The land and rights that were taken away from the Americans were partially restored after the indepedence of the states, in order to make a distinction from the Spanish rule, a period decribed below:

'Spain did pass some laws for the protection of the indigenous peoples of its American colonies, the first such in 1542; the legal thought behind them was the basis of modern international law. Taking advantage of their extreme remoteness, the European colonists revolted when they saw their power being reduced, forcing a partial revoking of these New Laws. Later, weaker laws were introduced to protect the indigenous peoples but records show they had little effect. The restored Encomenderos exploited the Indians rather than taking care of them.' (Source: Wikipedia).

Since the wars of independence fought in most South American states overthrowing the Spanish, widely lead by Simón Bolívar in the first part 1800's, oppression of the indigenous American population has been stemmed but there has been no overarching attempting to redress the crimes the indigenous peoples faced over the centuries nor reparations made. Today, Chávez's 'democratic socialist' model, he promises, is an attempt to establish some sort of equality in Venezuela and beyond, whilst providing a direct alternative to the world's trajectory of neoliberalism.

Regardless of Chávez's general politics, it is undeniable that his administration has done great deal for the poor Venezuelan population most conspicuously through the Plan Bolivar 2000, anti-poverty program carried out by the military, including mass vaccinations, food distribution in slum areas, and education, but also land reforms. Poverty is largely synonymous with the indigenous population in most of Latin America, as well as significant chunks of the mestizo population. So whilst I wander around admist beggars and poverty, I wonder 'is something major about to change for the majority of South Americans?' In Venezuela and Bolivia one could argue that it already has, through this land reform and redistribution of wealth. The self-proclaimed 'axis of hope' across South America is slowly widening, most recently with the election of Rafael Correa in Ecuador this November. Although European by ancestory himself, he sets himself apart from other Ecuadorian politicians by being able to speak a dialect of Quechua, Kichwa which is spoken widely in Ecuador.Despite this broadening coallition, Chávez faced the general election in Venezuela last week with some uncertainty: the cross roads. Had he lost, there is every chance a dam might have formed to cut off his 'red tide'. His challenger, Manuel Rosales, was credited with uniting a fratured opposition and he did represent a semi-serious threat to Chávez's grip on power. Possibly to the relief of the Venezuelan working class, in the end Chávez won the election by a subtantial margin - 61 percent of the vote.

We are now in Qosco, the oldest continually inhabitated city in the whole of South American and the capital of the sun-worshipping Inca empire correctly known as the Quechuan empire. Qosco therefore represents a heartland of the indigenous population, though of course Quechua people are just one of a huge number of pre-Colonial peoples. The Quechua language is still spoken spoken by 10 million people in South America, and unites a large proportion of indigenous peoples. Qosco isn't a bad place to reflect on the present situation for indigenous and mestizo lower classes, and to look at the resistance they made to colonial forces, to hold onto their identity and culture to the present day.

* * *On a personal note, before we arrived in Qosco we travelled around other parts of Perú and Bolivia. A few weeks ago James and I were in recovery mode from altitude sickness, tired and slightly frightened of the outside world. We felt that we'd arrived in the real Perú as we moped around the altiplano city of Puno. Following a very cold night in a single glazed bedroom, I didn't envy the local population who brave temperatures colder than those in the UK with fewer of the conveniences of home i.e. central heating. I was cold and this is summer! Insulation can't have been up to much, as in Puno and much of the Perú I travelled around many of the buildings look poorly constructed with single brick partions. Maybe this is an illusion of bare walls minus cosmetic plaster and paint. In any case, energy isn't available everywhere in the same quantity, I reckon a cold Perúvian winter so far above sea level is something to avoid.

This was our first taste of the Peruvian and Bolivian altiplano, an area at least 3000 metres above sea-level on a plateau atop the Andes. Despite the temperature at night, it's a place which it's very easy to get misty eyed and poetic about. Even considering the altitude sickness we suffered for a week on our ascent and the dried Alpcaca foetuses I saw on sale in the Mercado de las Brujas in La Paz, I've become very fond of this place. I've never seen anything like it before. The terraced mountain tops and the low cloud drift by silently while packs of sheep or alpacas are herded by women in traditonal dress. The comparitively sparse population and quiet life creates a deceptive impression of tranquility and ease. Life here would be tough. Looking out from with window of the coach as we travelled through along the southern edge of Lake Titicaca it seemed to me that life probably hasn't changed much for some of the campesinos in several hundred years. From Puno, along the edge of Lake Titicaca and across the Bolivian border, only small towns with tourist economies bring the 21st or even the 20th century back into focus. There was plenty to observe; day to day agricultural chores, local weddings (it was a Saturday), a bulldozer prettified with windchimes and bunting repairing part of the rooad and endless lonely dogs padding along the highway in search of food. Of course you don't notice the pestcides and modern livestock feed as you whizz past.

The altiplano has a unique yearning kind of atmosphere. Maybe there isn't too much outside interference here and people quietly get on with their own lives, but I doubt it.

This dreamland is shattered when you reach El Alto, a poor urban complex, but the fastest growing Latin American city which sits on the ridge above La Paz. It's ethnicity is typical of Bolivia's indigenous majority: 79% of its inhabitants are Aymara, 6% are Quechua. Things are raw here and the atmosphere seemed brutal compared to life by the lake. We passed the grim air force base and the dusty streets, as a game of football played by local women was cheered on by an enthusiastic crowd lightening the atmosphere. This didn't change the overall impression of deprivation.

El Alto is a place with much recent significance. During the Bolivian Gas War of 2003, 60 El Alto residents blockading roads and holding strikes were murdered by the armed forces. The gas war was certainly one of the events which significantly contributed to the election of Evo Morales this time last year. There is a good overview of the gas war here, but I will provide some background myself as in many ways it was an indigenous struggle.

The 'war' was brought about by the policies of Morales' predecessor bar one, Gonzalo Sánchez de Lozada. His hydrocarbon energy policy awarded 26 foreign companies (including BP) contracts to extract and siphon off Bolivia's natural gas via a pipeline leading through Chile. Lozada tried to implement this without going through congress, as is demanded by the consituttion. Bolivia has the second most abundant natural gas reserves in South America, and as liquified natural gas is widely seen as the next major energy provider once oil reserves become untenable, the fight over this resource was fierce and bloody. The indigenous majority of Bolivia widely opposed the 'looting' of their natural resources and wanted a larger proportion of profits from the sale of the gas than the measley 18% proposed. The argument of the incumbent government was that profits from the sale of the gas would bolster the Bolivian economy and be reinvested in health and education. They also suggested that only outside investment would be able to pay for the necessary infrastructure for the venture, providing jobs along the way. Most indigenous American Bolivians did not want their massive gas reserves exploited in the way that their silver and gold had been centuries before. They wanted the gas liquified in Bolivia (not in Chile as proposed - the country which wrested Bolivia's route to the sea) and domestic demand satisfied first and foremost.

In September 2003 the protests escalated and road blockades and strikes kicked in demanding the immediate resignation of Lozada. The gas issue also gave the indigenous majority an opportunity to vent their fury over Lozada's complicity towards the US War on Drugs, which proposed decimating coca crops, a vital part of native culture and livelihood. The government resistance culminated in mass direct action which successfully paralysed the country. In El Alto, strategically positioned as the entry point to La Paz, the county was brought to it's knees as food and fuel supplies were blocked. After 16 people were shot on a single day in El Alto, martial law was introduced by the government. These desperate measures saw Lozada's power slipping away and he suspended his gas project before resigning. His replacement, and previous Vice-President, Carlos Mesa promised a referendum and appointed indigenous people to some cabinet posts. The referendum, despite the support of high profile figures such as Morales supporting the vote, was widely seen as loaded and manipulative. It didn't allow a vote for outright nationalisation of hydrocarbons for instance. The result was that tens of thousands protested for full nationalization of hydrocarbons. The pressure reached boiling point and eventually Mesa also resigned, with Morales being elected in the subsequent elections of December 2005.

Here's one man's feeling on the proposed sale of the gas reserves to foreign big business, as he marched from Cochabamba to La Paz to protest against Mesa:

“People are suffering to get here as they have so little money. But I decided to come because we need to reclaim our natural resources. We have been robbed for centuries and our government is robbing us again.”' (Source: ZNet, Nick Buxton)

In this instance, but at no little personal cost, the indigenous population won. If the tide of neoliberalism can be stopped in it's tracks by a largely native American movement, then the politics of the continent are turning.

Whilst we were in La Paz, we had the oppportunity to look at a potent and controversial symbol of indigenous America: the coca leaf. The Coca museum was small but well researched and had an comprehensive written english guide to accompany the exhibits. The coca leaf is intricately linked with many aspects of prehistoric Andean culture and has been proved to have been used since around 2,000 B.C. The leaves were (and still are) used in socialising, worshipping and working. The coca plant was marked for eridacation by the Catholic church and categorised as 'diabolical'; a barrier to conversion of indigenous Americans to Christianity. These measures were quickly revoked when the Spanish realised they could use coca to exploit the workers - the stimulant effects of the plant made the slaves work harder in mines and on plantations as the plant relieved the symptoms of exhaustion and hunger. There was plenty of explanation of how coca was seen as a empowering symbol of resistance during colonial times, even though it simultaneously contributed to indigenous exploitation. It had secret weapon statues to the native Americans: it was considered poisonous to the white man and beneficial only to the native. Coca trading, chewing and production represented a state of mind, culture and spirituality. It was a method of keeping blood pumping through the veins of a, now clandestine, native way of life. It was therefore part of a resistance movement.

Because of it's use in cocaine, the coca plant (which is still, contrary to popular belief, used to flavour Coca Cola) is seen an albatross around the neck of South America by some economist and the source of their poverty. Coca production is targeted by the States as the source of it's huge narcotic problems. Needless to say the story is extremely complicated. In indigenous eyes, however, The U.S. sponsored annihilation of coca crops as part of it's War on Drugs, is seen as little more than neocolonial activity to keep the native americans down.

President Evo Morales is the head of Bolivia's cocalero movement – a union of coca leaf-growing campesinos who are campaigning against the actions of the United States government to destroy coca in the province of Chapare in southeastern Bolivia. Perhaps this is another aspect of indigenous life which has survived destruction and is returning to the top of the wheel of fortune.

Native resistance to invasion was born at the start of colonialisation and continues to this day. Inca Garcilaso de la Vega, himself a mestizo, was perhaps the first person to try and record some of history of Quechuan people and the Spanish conquest of Perú. His book 'Comentarios Reales de los Incas', was subsequently banned by Carlos III of Spain. Indigenous resistance for all native american groups from Canada to Cape Horn has a vast and fascinating history, there is an excellent article here.

Enabled by certain governments aboriginal American culture reasserts itself together with self-empowerment. A particularly inventive form of cultural reclaimation we observed was the Urban Virgins exhibition by Ana de Orbegoso at the Museo Inca, which employed the same assimilation of cultures the Conquistadors once used to subvert the lives of millions of people. Urban Virgins tries to superimpose indigenous culture on Catholicism, 'by removing classical European features from the face of the divine archetype in Peruvian colonial paintings, and replacing them with the images of present day Peruvian women.' An example of the colonial tradition this lampoons, is to be found in the former Quechuan shrine Qorikancha in Qosco. It was once the very centre of the Inca empire which stretched out north to Colombia, south to Chile and east to Argentina. Once the Spanish arrived they partially destroyed the shrine and built a Dominican Monastery on the top.If a corner is being turned to a better future for indigenous American people we will know it when the poverty which is spread across the continent is hugely diminished. Here are some photos of life in South America today as we've seen it: A girl from the reed constructed Uros Islands rows a boat on Lake Titicaca. I imagine the kids are taught to be self-sufficient from a young age. Whilst we were on the islands we got an idea of how the islanders have adapted to use tourism for their survival.

A girl from the reed constructed Uros Islands rows a boat on Lake Titicaca. I imagine the kids are taught to be self-sufficient from a young age. Whilst we were on the islands we got an idea of how the islanders have adapted to use tourism for their survival.

Some of the kids who are taught at their local school to sing in 6 different languages rowed up to us in their boat and gave us a show. They looked a little timid and probably would have preferred to be somwhere else, but their show didn't last that long and they got some money. I had to do a lot of things I didn't want to do when I was their age! Support for Evo Morales, in a surprisingly posh suburb south of La Paz by Valle de La Luna. Indeed Evo's election was undeniably a watershed in South American politics. He is the country's first indigenous head of state since the Spanish Conquest over 470 years ago. Shortly before we arrived in Bolivia, Morales' land reform legislation had been passed. Morales has been considered as too moderate by some of the left for his preparedness to negotiate over the nationalisation of hydrocarbons (which he eventualy achieved) and as a strategic radical posing as a moderate supporter of democracy by western economists.

Support for Evo Morales, in a surprisingly posh suburb south of La Paz by Valle de La Luna. Indeed Evo's election was undeniably a watershed in South American politics. He is the country's first indigenous head of state since the Spanish Conquest over 470 years ago. Shortly before we arrived in Bolivia, Morales' land reform legislation had been passed. Morales has been considered as too moderate by some of the left for his preparedness to negotiate over the nationalisation of hydrocarbons (which he eventualy achieved) and as a strategic radical posing as a moderate supporter of democracy by western economists. Plaza Pedro D Murillo, La Paz. James and I frequently encountered military marches and presence in Bolivia. This is the country which has suffered more military coups than any other, a staggering sixty! You can only imagine how tired of disorder and uncertainty the population must be. To what extent Morales achieves his political aims with the help of the military, or how long he might hang on to power if he is out of favour with it, must be at the back of most Bolivian's minds.

Plaza Pedro D Murillo, La Paz. James and I frequently encountered military marches and presence in Bolivia. This is the country which has suffered more military coups than any other, a staggering sixty! You can only imagine how tired of disorder and uncertainty the population must be. To what extent Morales achieves his political aims with the help of the military, or how long he might hang on to power if he is out of favour with it, must be at the back of most Bolivian's minds. Puno, a Peruvian town on the edge of Lake Titicaca. When we first arrived in Puno, a city of about 100,000 people, it seemed like the real Perú to me and James. James is probably fed up of me describing the population of of places in terms of the number of times bigger our location is than Windsor, by now. I suppose the change we were observing was between low-land and campesino lifestyle. Puno has gringo infrastructure, mainly Avenida Lima, an area crowded with restaurants and souvenir shops with you might find in any tourist resort, but the atmosphere feels different to the coastal desert region.

Puno, a Peruvian town on the edge of Lake Titicaca. When we first arrived in Puno, a city of about 100,000 people, it seemed like the real Perú to me and James. James is probably fed up of me describing the population of of places in terms of the number of times bigger our location is than Windsor, by now. I suppose the change we were observing was between low-land and campesino lifestyle. Puno has gringo infrastructure, mainly Avenida Lima, an area crowded with restaurants and souvenir shops with you might find in any tourist resort, but the atmosphere feels different to the coastal desert region. A traditional welcome on one of the main floating Uros floating islands. We were treated to this as we arrived on our boat. Because of the novel way in which they live, the Uros people are perhaps more familiar to tourists than surrounding native peoples. With no islands in Titicaca left to occupy, the Uros made their own out of reeds, which they continue to do to this day! They speak Aymara after their own Uro languge died out, whilst trading and intermarrying with those on the shore. The Uros people were forced out into Lake Titicaca not by the Spanish, but in fact the Quechau, who threatened their lives. I do not mean to create the impression in this post that all pre-colonial America was a place of harmony. It most certainly was not. That does not diminish the impact of colonisers who eclipsed and swamped all existing peoples to the point of genocide.

A traditional welcome on one of the main floating Uros floating islands. We were treated to this as we arrived on our boat. Because of the novel way in which they live, the Uros people are perhaps more familiar to tourists than surrounding native peoples. With no islands in Titicaca left to occupy, the Uros made their own out of reeds, which they continue to do to this day! They speak Aymara after their own Uro languge died out, whilst trading and intermarrying with those on the shore. The Uros people were forced out into Lake Titicaca not by the Spanish, but in fact the Quechau, who threatened their lives. I do not mean to create the impression in this post that all pre-colonial America was a place of harmony. It most certainly was not. That does not diminish the impact of colonisers who eclipsed and swamped all existing peoples to the point of genocide. A message in the reeds on the Uros Islands, Lake Titicaca. This curio has been dusted off for tourists, but the orignal intention of these reeds hanging down from the line was to communicate to other islanders without them having to come 'ashore'. The number and length of reeds would indicate whether the island was occupied and how well stocked it was with food, for example. Like many traditions, preserving elements of a lifestyle via tourism is not a very good method - everything is for show - but it is one that is available. I bought a shawl sewn by one of the women on the island for 50 soles. It is better to buy from the source rather than going through a shop. For the smaller societies tourism is likely to remain the main way of preserving a (somewhat amended) way of life for many years to come.

A message in the reeds on the Uros Islands, Lake Titicaca. This curio has been dusted off for tourists, but the orignal intention of these reeds hanging down from the line was to communicate to other islanders without them having to come 'ashore'. The number and length of reeds would indicate whether the island was occupied and how well stocked it was with food, for example. Like many traditions, preserving elements of a lifestyle via tourism is not a very good method - everything is for show - but it is one that is available. I bought a shawl sewn by one of the women on the island for 50 soles. It is better to buy from the source rather than going through a shop. For the smaller societies tourism is likely to remain the main way of preserving a (somewhat amended) way of life for many years to come. In this picture the tourists and locals mix on Taquile Island, Lake Titicaca. It was part of the Quechuan empire and held out against the Spanish for a long time. Eventually when the Spanish arrived the Taquile residents were forced to adopt the traditional Spanish dress they still wear today. The island today runs on the basis of Quechuan collectivism, but it also relies on tourism. Plenty of tours like ours arrive everyday to wander around the island and buy the textiles and clothing they produce. When we arrived there seemed to be more division between the tourists and the locals than on the Uros Islands. The people were not unfriendly but they tolerated tourists rather than embracing them. They do have a specially recreated gringo invasion every single day... The local children were persistant in selling what I know as 'friendship bands', which is to be expected. The grumpy reaction and snapping of some of our fellow tourists in the group, I thought was unnecessary and frankly ignorant.

In this picture the tourists and locals mix on Taquile Island, Lake Titicaca. It was part of the Quechuan empire and held out against the Spanish for a long time. Eventually when the Spanish arrived the Taquile residents were forced to adopt the traditional Spanish dress they still wear today. The island today runs on the basis of Quechuan collectivism, but it also relies on tourism. Plenty of tours like ours arrive everyday to wander around the island and buy the textiles and clothing they produce. When we arrived there seemed to be more division between the tourists and the locals than on the Uros Islands. The people were not unfriendly but they tolerated tourists rather than embracing them. They do have a specially recreated gringo invasion every single day... The local children were persistant in selling what I know as 'friendship bands', which is to be expected. The grumpy reaction and snapping of some of our fellow tourists in the group, I thought was unnecessary and frankly ignorant.

28th November 2006, Day 253

28th November 2006, Day 253

Arequipa, Peru

I'm a bit ill today. This is the first time I've felt off colour since I was in India back in March/April, so I'm not doing too badly really. We arrived in Arequipa - the white city, constructed from white sillar stone - yesterday after another of the over night bus rides you'd really rather avoid. Arequipa is 2,300 metres above sea level and that's the sort of height where altitude sickness kicks in. After feeling tired all day we cooked some spaghetti in our hostel's dodgy kitchen. A night of many trips to the toilet and an aching stomach followed. I was then woken up at midday by someone rattling the bedroom door violently. When I went to find out just what was going on, I realised that the ground was shaking due to a small tremor. Very foreign!

Nazca, which we've just left for Arequipa, is the most noteworthy place I've been to in Peru so far. Many people are familiar with the Nazca Lines - large land drawings or geoglyphs which can only be appreciated from the air. In fact the geoglyphs cover over 200 square miles. The purpose of these lines has been the subject of much debate and wonder. The huge figures include a monkey, a hummingbird, a spider, a condor, a dog etc. Sadly before the lines were rediscovered by Dr. Paul Kosok in 1939, the Peruvian stretch of the Pan American highway had already been built right through part of the lines. You can see a photo of the road next to the geoglyphs of James' latest blog entry. Despite many years of research since the lines were rediscovered, no scientific conclusion has been reached as to why the lines were built in the first place. The main theories are thus:

1. Maria Reiche. The first major researcher (her archeological partner Dr. Paul Kosok stopped work on the lines in 1948) and one of the most respected, Maria believed that the lines were primarily an astronomical calendar, with geoglyphs for summer (the Hummingbird) and winter (the Condor) equinox. The geoglyphs calibrated the year into a calendar and made sense of the heavens by tracking their movement - a unique observatory.

2. David Johnson. David is still conducting research but believes that the lines referred to where subterranean water could be found in this arid location - in other words the Nazca lines are a giant water map. The large pointing arrows supposedly indicate under ground sources of water.

3. Robin Edgar. Robin theorised that the Lines were a response to an unusal period of solar eclipses that took place around the time when the Nazca Lines are suspected to have been constructed. The geoglyphs were to be seen by a giant 'Eye in the Sky' - which is the way that the sun and moon might have appeared to the Ancient Nascas during a total eclipse.

4. Jim Woodman. This theory is based around the feeling that something as large as the Nazca Lines could only have been produced for an aircraft's perspective. Woodman managed to construct a hot air balloon from materials and techniques available at the time, to add strength to his argument.

5. Erich von Däniken. Erich believed that the lines were created as runways for Alien spacecraft. I think this is a cracking idea. This photo of the monkey geoglyph was taken by the Peruvian airforce photographic service on behalf of Maria Reiche. In the late afternoon of our first day in Nazca, I had the good fortune to stumble across Viktoria Nikitzki, who runs the Maria Reiche centre which is also her home. We were looking for the centre - mentioned in the Lonely Planet - and had no idea who the busybody was staring us down outside a dusty brick building. 'Is that your washing? I can help you with that... if you are here for my lecture.' We were indeed looking to kill two birds with one stone, so she called out to one of her nieghbours cycling past and soon our dirty linen had been taken in by some bemused local women, who blinked in uncertainty at two sunburnt gringos. Aside from getting our washing done, Viktoria turned out to be one of the most mysterious and compelling people I've ever met. She was a personal friend and disciple of Maria Reiche. We agreed to meet her later for the lecture, and went back to our poorly ventilated and hence smelly hostel. I'll name and shame the place actually - Alegria II - the sheets were dirty and I would compare the smell of our room to vinegar mixed with dirty socks. Foul.

This photo of the monkey geoglyph was taken by the Peruvian airforce photographic service on behalf of Maria Reiche. In the late afternoon of our first day in Nazca, I had the good fortune to stumble across Viktoria Nikitzki, who runs the Maria Reiche centre which is also her home. We were looking for the centre - mentioned in the Lonely Planet - and had no idea who the busybody was staring us down outside a dusty brick building. 'Is that your washing? I can help you with that... if you are here for my lecture.' We were indeed looking to kill two birds with one stone, so she called out to one of her nieghbours cycling past and soon our dirty linen had been taken in by some bemused local women, who blinked in uncertainty at two sunburnt gringos. Aside from getting our washing done, Viktoria turned out to be one of the most mysterious and compelling people I've ever met. She was a personal friend and disciple of Maria Reiche. We agreed to meet her later for the lecture, and went back to our poorly ventilated and hence smelly hostel. I'll name and shame the place actually - Alegria II - the sheets were dirty and I would compare the smell of our room to vinegar mixed with dirty socks. Foul.

We returned to Victioria's spartan home at seven o'clock for the evening lecture, by which point it was dark. We stumbled through a dimly lit and ramshackle anteroom into her 'lecture theatre', the largest room in the house with a mud floor and single lamp to light a scale model of the Nazca Valley. This came in to view gradually as the light warmed up. Barely had James and I settled down on the stone bench before Viktoria rejoined us. Unprovoked, she doled out what I would call 'a piece of her mind' to James and I. I didn't mind, however. I received the impression that she would just have easily have shared the same information with a three year old or a mafia stooge pointing a gun at her head. To put it simply she didn't give a toss. Being a bit of a wimp myself I always admire this attitude in people. We talked a little at the beginning about South American politics whilst we waited for some other customers who ultimately never showed up: she praised Chavez and Morales, but employed a grave tone to describe the former's relationship with Castro. She declared Cuba to be the only Latin American country with a monarchy! Aside from that, all bitterness was directed against Bush, and his attempts to unsettle the fledgling neo-socialist movement spreading across the continent. Her speech was littered with frowns, knowing looks, pregnant pauses and grins. She had a well-turned 'woe is me' element to her character which she brought up now and again to her advantage. She was deliberately comedic, then suddenly serious as she talked about her effort to 'save' the lines without the tools to do it. She painted a picture of herself surrounded by unscrupulous bureaucrats and nincompoops. Maybe it was true.

You could describe Nikitzki as 'weird' I suppose. James had a number of intelligent questions to ask about the lines that she simply didn't answer because it wrested the perogative away from herself. I'm not doing the best job of making her sound charming, but she was to me (although I sympathised with James, who still valued the experience). Clearly European by origin, I asked Viktoria where she was from - 'I am from cosmos' she replied. I suspected that she might have been German like her friend Maria Rieche, but James reckoned she was French on the basis of her gesticulations. She went on to talk about her neighbours, one of whom sells Coke on the street side, while her teenage daughter goes to discos (she will be pregnant within the year according to Viktoria - she's sounds like a conservative politican from 1991 now doesn't she?). She scruched up her face. Within Viktoria's 'cosmos' Coca-Cola does not exist. A brief digression. Around here Coke is delivered in tank like vehicles and they sponsor the street signs. There's not much competition in Peru, everything in the supermarket seems to be made by a few companies - mainly Coke, Nestle or Unilever.

A brief digression. Around here Coke is delivered in tank like vehicles and they sponsor the street signs. There's not much competition in Peru, everything in the supermarket seems to be made by a few companies - mainly Coke, Nestle or Unilever.

The local 'Inca Kola' used to have much bigger share of the soft drinks market in Peru than Coca-Cola, so they bought them out. The same happened in India with a cola drink called 'Thums Up'.

Coke make a big deal of the fact they are franchised on a country by country basis supporting local economies. So they're not a multinational at all, see? Why do they have a CEO and international board of directors then?Enough of my pet obsessions.

Back to the Maria Reiche centre. To elaborate on my earlier point, the mian thing Viktoria lamented about Peru was the endemic corruption and the poor education which has hatched an aquiescent attitude among the poor (which is the overwhelming majority of the population). She described a hypothetical situation in which an official might spit upon a local: 'hmm, perhaps the wind blew the wrong way' would be the response of the average Peruvian, she thought. She'd recently heard (we think incorrectly) that there was an attempted coup against Morales in Bolivia and she was upset that there was no one in Nazca to discuss it with. Her dignity refuses to allow her to leave Nazca. Having met her I felt she was isolated and I pitied her a little, which she would have hated.

OK... so what about the Nazca Lines? That was the point of the lecture, wasn't it? We did get onto them eventually. Gratitude. That summed up what the lines were about according to Viktoria (she was doing a good job of talking from her own perspective not Maria Reiche's, but this was clear with a bit of research). In what way were the Lines about gratitude?

The lines were built by Ancient Nazca civilisation (300bc-800ad) from which the site now take it's name. According to Maria Reiche, who studied the lines for 50 years, they an elaborate astronomical calendar created to mark risings and settings of the sun, moon and stars. This is outlined in her publication 'Mystery on the Desert' (first published in 1949). The crux of Reiche's work was based around where the sun's rays fell during sunrise at Summer and Winter equinox. The Hummingbird (which is associated with the warm summer months) was built at the point the sunlight reached at summertime and the Condor with it's huge beak the winter solstice. This was also a place for ceremonies to celebrate life and give thanks for it.

We moved onto hydrology. I may be wrong, but it seemed Viktoria again mixed her own opinion with that of Reiche; at least so far as we can tell in Reiche's book. Viktoria talked about water - large triangular pointers were 'drawn' to signify locations of subterrean water ways (also proposed by Johnson). Viktoria produced some divining rods and two bottles of water, at this point - one full the other half full. After waving some rods around a bit she demonstrated the art of divining... if you were prepared to use your imagination a bit.

I hope I am not being too facetious about Viktoria; really the bulk of her work is pretty serious, and I am not trying to make light of that. Quirks and foibles are what gives a personality colour, which is why I mention them. I truly admired her, even if I did take a little of what she said with a pinch of salt.

A wonder of the world (though not in any official sense), the huge geoglyphs probably won't be around for decades to come. Viktoria is negative about the future of the lines. She is convinced they are being destroyed. In recent years the inhabitants of Nazca have been dumping their rubbish, (plus that left by tourists) on the pampa or plains. How long before it becomes a huge mountain the eats up the 'glyphs? More importantly, as Maria Reiche pointed out as long ago as 1976, the area, which was previously almost rain free, has been receiving increased precipitation year on year for long time. In Viktoria's words:

"There has been deforestation everywhere so water from the highlands comes down to the Lines in streams and rivers. The Lines themselves are superficial, they are only 10 to 30cm deep and could be washed away. There is no maintenance or any sort of care for the Lines. Also there is threat by the weather. Nazca has only ever received a small amount of rain. But now there are great changes to the weather all over the world. The Lines cannot resist heavy rain without being damaged."

The Nazca Lines are supposed to be a UNESCO world heritage site, which means they should receive some form of funding to help preserve them in the long term. Viktoria is adamant that no work is being done to protect the lines, and thinks that UNESCO is a load of nonsense. She reckons whatever money might be received for the protection of the lines goes straight into the pockets of Peruvian politicians, civil servants or officials. The Maria Reiche Centre is calling for international intervention to protect the geoglyphs, and wants local pollution controls and irrigation systems to divert water away from them. Viktoria doesn't think they'll listen to her, despite endless letters and overtures to government departments, archaeological and environmental groups.

Before we left her for the evening, Viktoria intentionally sent us on a guilt trip about wandering away from her lecture without doing anything to support the cause of the Lines. The following day I returned to Viktoria's house to help cut down what she called 'the Espinola tree' in her backyard (NB: removing the tree and preserving the lines may not be directly related). Armed with a vicious machete I set about this task whilst trying to avoid her pet turkey and kittens with the falling foliage. 'No! Too big, you must chop it up and throw over the back wall' were Viktoria's barked instructions when I lopped off the first large branch. I spent three hours being scratched by large thorns and balancing precariously on a crumbling brick walls, so this was a bit of a fool's errand. The thing is, I do take the odd measured risk, and this was not comparable to an Evil Kneivel stunt. I just wanted to put Viktoria's mind at rest as she continually referred to some (possibly exaggerated) security threat - she thought people could climb into her sealed yard via the low hanging branches. Anyway, I laboured away for a while with the help of another German volunteer and got rid of the best part of the tree. 'My cat will be waiting for you when you get down if you drop a branch on him', said Viktoria with a toothy grin which reminded me of Mark E. Smith.

James turned up fresh from his flight to help for the last half an hour or so, and Viktoria was grateful for the work. We were rewarded with some jam she made from the pods of the tree I was chopping down.

In the afternoon, after I washed off four years of dust from 'the Espinola tree' and went for a more affordable tour of Nazca than the flights. My guide Jan (short for Janssen not Juan), was a trained archaeologist and a very pleasant guy to boot. He was about my age and we got on very well. Before we set off, I tried to verify some of the general points Viktoria had made with Jan. He agreed that there were huge problems with corruption, but thought that the situation was a little more complex than Viktoria suggested - particularly education on historical sites in Peru for Peruvian nationals. He had a distinct personality to Viktoria; I asked him what his pet theory on the Nazca lines was and he said 'nothing is believed until proven in archeology.' I was going to receive a very different perspective.

Before we started the tour I wanted to find out a little about Jan and he appreciated the opportunity to take his tourist guide hat off for a moment. Jan talked a little about the basketball coaching he did on Saturdays for a couple of hours in a poor village near Nazca. He wasn't too downbeat about the country's future and talked about his wife and child and his ambition to get back into archeology and work in Egypt. He also talked about how much he loved the Rolling Stones and the rock band he was in himself. When 'I'm Free' hollered by a young Jagger came on the radio in van on the way back, I thought he was going to punch the window in joy.

Our first stop was at the aqueducts, built by the ancient Nazcas (300bc-800ad). I am not totally certain but I believe these were built to preserve and improve access to natural waterways. Channels were cut down into the turf at the point which the water was closest to the surface. They were an amazing feat of engineering. Reeds which grew up from the large stone banked channels, blocking the passage of the water were cut away each year by the Nazca population, with individuals travelling down inside the meadering and fractured subterranean channels. It was a job which was delicate and very dangerous. Very few of the orginal aqueducts have been repaired or altered and they are still used today. A mark of the quality of the water is the numerous little fish which you can see swimming in the channels. Spiral walkways were built down to some of the openings for carrying large water containers down to the water and back up with ease (some wells were as deep as 20 metres).

Next we travelled on to some of the outlying geoglyphs; places not covered by UNESCO status. Jan talked for a while about the established uses of the Lines of which there is really just one. They were definitely used in ceremonial rituals of one kind or another, their other purposes are open to theory. This has been established via a myraid of fine ceramic found in all the geoglyphs. Jan was more concerned about the plight of these geoglyphs and the rubbish dumping I mentioned before, than what is happening to the better known lines which the plane tours cover each day.

One surprising thing is the limited industry in the area. Jan showed me some of the iron and aluminium ore which is abundant here. Also present is copper, silver and even gold. Indeed there is one gold mine owned by Canadians heading towards Cusco, and Peru is major player in extracting some of these metals. Frankly I'm amazed, however, that this area isn't off limits having been sold to hard rock mining companies. I understand that hard rock mining is nowhere near as easy and profitable as mining for fossil fuels, but if we are talking about copper (because of the components of modern electronic devices) and gold, well, that's a different and more profitable matter.

Now we step forward dramtically in time. At our final stop we looked at some of the much later Inca Empire's (1197ad-1533ad) construction in the area. Las Ruinas de Paredones, are the remains of an Incan fort built around 1412 from which the head 'Inca' who ruled the whole settlement could view the whole Nasca valley. It was quite a vantage point.

I was charged a fee of ten soles to visit all the places Jan took me, but evidence showed the behaviour of some tourists who visited these places was poor. The site with it's crumbling bricks were not supported or off-limits to tourists at any point. Peru always has a major battle on it's hands because earthquakes frequently destroy relics of it's rich historical past. Indeed that's the main reason Los Paredones looks the way it does today. That doesn't excuse people walking along the walls, scratching their names in the mud brick or leaving their rubbish in the site itself. 'At least people don't play games of football here any longer', sighed Jan. He made a big point that most destruction of important geological sites in Peru was caused by national rather than international tourism. Whilst we looked at the mud bricks I saw plenty of western names scratched into the former walls, though.

As we headed back into Nazca itself Jan invited me to watch him play basketball that evening and I gladly agreed. I don't know much about Peruvian basketball, needless to say! Sadly James and I had to skip town that night, as the only buses to Arequipa were at night and we didn't fancy kicking our heels in Nazca for another day. When I went to meet Jan to offer my apologies he turned up happy and smiling with his wife and small child. He accepted my excuses with good grace, but I felt like a right idiot.

A few more pictures. The aqueducts built around Nazca by the Ancient Nascas have been well preserved and as you see, are still in use today! Jan chatted to these local guys who were knocking around on Saturday afternoon eating Mango Verde with salt. They knew what I was getting at when I stuck my tongue out in revolt. In fact I thought we were establishing some level of rapport when Jan indicated it was time for the geoglyphs.Other things we've done in Peru...

A few more pictures. The aqueducts built around Nazca by the Ancient Nascas have been well preserved and as you see, are still in use today! Jan chatted to these local guys who were knocking around on Saturday afternoon eating Mango Verde with salt. They knew what I was getting at when I stuck my tongue out in revolt. In fact I thought we were establishing some level of rapport when Jan indicated it was time for the geoglyphs.Other things we've done in Peru...

Our first port of call after Lima was Pisco (famous for it's grape of the same name). Just below Pisco lies the Parracas peninsula from where you can catch a boat to it's primary tourist attraction, the Islas Ballestas. These isles shelter a veritable feast of wildlife, with Pelicans, Emperor Penguins, Pelicans, Boobies and Sealions. We got some great snaps.

Our first port of call after Lima was Pisco (famous for it's grape of the same name). Just below Pisco lies the Parracas peninsula from where you can catch a boat to it's primary tourist attraction, the Islas Ballestas. These isles shelter a veritable feast of wildlife, with Pelicans, Emperor Penguins, Pelicans, Boobies and Sealions. We got some great snaps.

Emperor Penguins on Islas Ballestas. One of the most surprising things about the islands was how intermingled all the different bird species were, boobies, penguins, pelicans and cormorants all stood side by side, apparently not bothering one another.

Emperor Penguins on Islas Ballestas. One of the most surprising things about the islands was how intermingled all the different bird species were, boobies, penguins, pelicans and cormorants all stood side by side, apparently not bothering one another.

This is Huacachina, a desert town (which exists for tourists) built around an oasis. We stopped here for the sandboarding that we read about in our Lonely Planet. This involved travelling in a the kind of sand-dune buggy they warn you not to get in on the Foreign and Commonwealth office website. Hey, it had roll cage! The actual boarding (very similar in principle to snowboarding) was not easy. We had several opportunities to throw ourselves off dangerously steep banks, with next to no guidance and no skiing or snowboarding experience necessary. There's a great shot of me rolling down the dune with my bottom hanging out. With much charity James didn't publish it on his blog.

This is Huacachina, a desert town (which exists for tourists) built around an oasis. We stopped here for the sandboarding that we read about in our Lonely Planet. This involved travelling in a the kind of sand-dune buggy they warn you not to get in on the Foreign and Commonwealth office website. Hey, it had roll cage! The actual boarding (very similar in principle to snowboarding) was not easy. We had several opportunities to throw ourselves off dangerously steep banks, with next to no guidance and no skiing or snowboarding experience necessary. There's a great shot of me rolling down the dune with my bottom hanging out. With much charity James didn't publish it on his blog.

11th November 2006, Day 235

11th November 2006, Day 235

Santiago, Chile

I write this as a nervous and hungover shell of a man. A merry night out in Barrio Bellavista with Roberto, our friend and part-time tour guide, went a bit wrong when I slipped into the bad old ways and drank far too much Chilean lager. I don't remember whether the band we saw, Espia, were up to much, but I do remember talking a lot of nonsense to Roberto and his mate. Despite a comfortable week of cultural assimilation, today I nervously staggered around in the blinding light of the midday Santiago sun having forgotten all the vocabulary I'd learnt in the expensive Spanish classes we'd taken and reverting to apprehensive alien status. Indeed I felt feeble and rather crass. This is my chance to redeem myself.

We are, of course, now in South America. This has dragged me out of a package tourist ditch which I'd complicitly slid into in Australia and New Zealand. It doesn't feel like I'm halfway home any longer, these four months will be a challenge I've not hitherto experienced during these travels. Some of the stereotypical adjectives associated with Latin America (vibrant, colourful), are not especially appropriate for Santiago, which is widely regarded as one of the most European cities in atmosphere in the sub-continent. It is, however, a massive change from the last three months of familiarity and also a land where the majority of people do not speak English. Good lord!

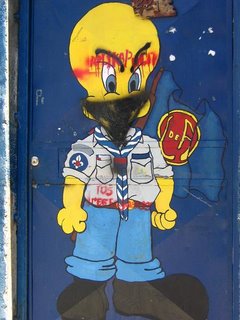

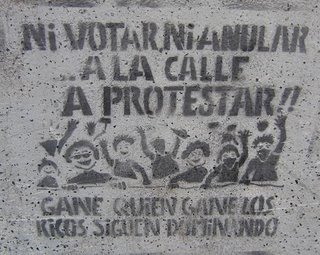

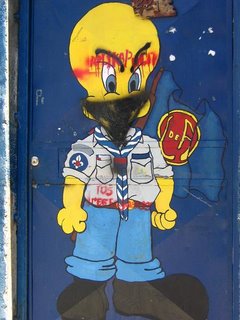

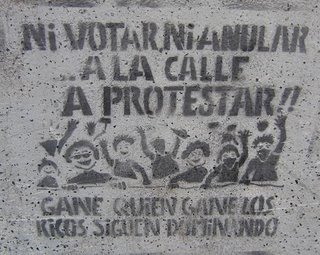

Fortunately I have a muse (of the online variety) and consequently I have thought of something to write about. Instead of opening this post with a nice view of Santiago cupped by the Andes and the coastal mountains, I've challenged myself to do something less obvious. So here's Tweety Pie masked up and ready to go. As you may be aware Santiago amd Chile itself has recently been shaken from, what I would imagine, is it's usual orderly and efficient day to day business. During May student strikes, starting with direct action in April, reached a peak with minor riots breaking out. On 1st June President Michelle Bachelet announced some educational reforms which met many of the student's demands and the strikes were called off by student leaders. The pace of the introduction of the legislation is still causing problems, however. The dust has yet to settle on this predicament and the city walls bear plenty of evidence of unrest over the last six months. I'll have to ask for a correct translation of this, but with the help of an internet translator, this stencil says something like, 'Neither vote nor annul, get on the street and protest! The rich continue to prosper'. This revolt captured the imagination and creativity of the students as well as cultivating a little rebellion for rebellions sake. We've seen this through the grafitti artwork around the city, student interest in political theory and systems, vandalism and a heavy police presence on the street. I don't think I've ever seen so many anarchy symbols in one place, for what that's worth.

I'll have to ask for a correct translation of this, but with the help of an internet translator, this stencil says something like, 'Neither vote nor annul, get on the street and protest! The rich continue to prosper'. This revolt captured the imagination and creativity of the students as well as cultivating a little rebellion for rebellions sake. We've seen this through the grafitti artwork around the city, student interest in political theory and systems, vandalism and a heavy police presence on the street. I don't think I've ever seen so many anarchy symbols in one place, for what that's worth.

There is a lengthy article on the strikes hosted on Wikipedia; events which have become known as 'the March of the Penguins' in reference to the student's uniforms.

James and I have seen a lot of the students ourselves whilst wandering around the city. Staring is a more accurate term than seeing, really. The girl's uniform is rather revealing around the top of the leg. This is not really appropriate behaviour for two men approaching 30. Regardless, the students are verging on the ubiquitous and I would imagine that combined they were a formidable force a few months ago.

Chile has a large proportion of young people, a quarter are 14 or under for instance. According to the Wikipedia article (I should really use another main reference):

'The country suffers from a rigid class stratification issue, with a poor majority of close to 60%, although extreme poverty rates declined in the 1990's and today accounts for close to 20%.'

The quality of state education is generally viewed as poor among Chileans. Add this to the central legislation around teaching introduced by the Pinochet regime (the Constitutional Teaching Law) which has not been altered much in over 15 years of democracy and you begin to identify some of the catalysts for this incident. Whilst literacy rates in Chile are extremely high, the public perception that state education in Chile is poor is strong and increasing according to the articles I've read. Half of all those students who finish their high school education fail to gain access to higher education via an entrance exam, or can barely afford the test at all.

Whilst literacy rates in Chile are extremely high, the public perception that state education in Chile is poor is strong and increasing according to the articles I've read. Half of all those students who finish their high school education fail to gain access to higher education via an entrance exam, or can barely afford the test at all.

One columnist commented that the crux of the strike lay in the fact that while the private schools turned out the wealthy, the state schools churned out workers to preserve a long established class system.

The Organic Constitutional Law on Teaching (LOCE), which I mentioned above is criticised for:

'reducing the state's participation in education to a solely regulatory and protective role, whilst the true responsibility of education has been transferred to private and public corporations (public schools being managed by local governments — Municipalidades), thus reducing the participation that students, parents, teachers and non-academic employees had previously enjoyed in their schools.' Source: Wikipedia.

Revoking of the LOCE was the big ask of the students. In simple terms the direct action could be seen as a fight for simple educational change or representation in government decision making. Among the more progresive and radical elements it was undoubtedly seen as a fight against the government or indeed the beginnings of a class war.

The ultimate catalyst for this year's unrest was Michelle Bachelet's announcement towards the end of April that the university entrance test (PSU) fee would increase and free student bus travel would be restricted. General anger from state students boiled over. Outrage, intial demonstrations and school takeovers followed. In the subsequent weeks the Coordinating Assembly of Grade School Students (ACES) organised the strikes with the following demands:

- free bus fare

- waiving of the university admissions test fee

- the abolition of the Organic Constitutional Law on Teaching (LOCE) and an end to municipalization of subsidized education

- a reform to the Full-time School Day policy (JEC)

Considering that these were young school children it's not surprising that action was diverse and sometimes lacked clarity. Depending on your opinion some actions could even be labelled blockheaded at times (ostensibly unecessary violence and vandalism), but this youthful melting pot also spawned the vision I mentioned above. Indeed those protests which turned violent intially dampened public sympathy for the pupil's plight. The kids carried on with their tightly organised occupations and held discussions on political theory and civics inbetween their regular classes. I wonder how many became committed Communists or Anarchists during this time? Over the following days, the student's dedication and perseverence gradually won their actions tolerance and their aims respect among Chileans. The stubborn attitude towards the students demands by the government coupled with a focus on non-violent direct action eventually began to change this public perception, from what I can tell. Education minister Martin Zilic, for instance, proved particularly non-communicative and surly towards the students aims, breaking off negotiations and sending deputies to negotiate with student leaders in his place as the stand off worsened.

I spoke to two Chileans about the strikes. One a friend and university student and the other our Spanish teacher. They both generally supported the strikes. Indeed the strike called by the students and arranged for the 30th May was the largest in Chilean history, with the main Santiago-based Universities in support. The second strike on 5th June comprised teachers and many unions as well as the students. According to a poll 87% of Chilean's voiced support for the strikes, at their height. Diverse acts of rebellion ranged from occupations and marches to rallies and street fighting.

On the 30th May, the day of the largest strike, the greatest concentration of violent clashes took place. The force of that the caribeneros (uniformed police) employed to deal with violent students and rioting pockets was widely criticised as over the top and effectively incendiary:

[On the 30th May] 'Fighting extended throughout the night, with 725 people arrested and 26 injured. The actions of the police were strongly repelled by the public. Some of the strongest reactions came from the press and the President herself.' Source: Wikipedia.

As a result of the way the Carabineros tackled the riots, the general director of Carabineros dismissed ten officers including the Special Forces Prefect and his deputy.

The things which shock me about the uprising are two-fold. Firstly the organisation and scale of the mobilisation coupled with the age of those organising (average age 16) is a surprise. Mobile phones, text messaging and email were the tools they employed. There is a related article about how the children organised themselves here, which contains links to the various student's blog sites divided by school. It is notably creative, spontaneous and encouraging. There are some particularly striking photos here. The strike of the 30th of May comprised up to a million students! I find this quite staggering for a movement which was barely a month old by the time it successfully mobilised a generation of children.

Secondly they have, to some extent, won. After Bachelet's reforms, hastily announced on 1st June, subsequent delays in introducing legislation are almost over. According to my friend  'legislation has been passed regarding scholarships for the PSU(university entry exam), it is now free for the poorest half. The reduced bus fare for school kids now runs 24 hours.' Criminal charges against individual student leaders were dropped. My friend points out this may have been to prevent a student backlash. Some of these Assembly leaders were extremely young, such as María Jesús Sanhueza, an outspoken 16 year old Communist.

'legislation has been passed regarding scholarships for the PSU(university entry exam), it is now free for the poorest half. The reduced bus fare for school kids now runs 24 hours.' Criminal charges against individual student leaders were dropped. My friend points out this may have been to prevent a student backlash. Some of these Assembly leaders were extremely young, such as María Jesús Sanhueza, an outspoken 16 year old Communist.

The long term goals for education, such as the abolition of LOCE, are still under discussion. There are still problems with the student leaders on Bachelet's panel who do not necessarily have the backing of the students that they previously held. The political awakening and ambition that has been aroused in these children may be satisified through negotiation and engagement with the government, but perhaps it won't.

Having spoken to university student and a teacher, there is a mixed opinion about the events in retrospect. My uni student friend said:

'It's great, this generation of kids are the first to be born since the return of democracy, so they don't have any of the prejudices generations like mine must have, they never knew a military goverment and that may have something to do with their active political participation. I can see my generation being much more apathic politically.'

My teacher was more sceptical, despite a general sympathy. He thought that completely free bus travel at all times was too much to ask, and that the students long term ambitions were naive. I suspected he strongly objected to any violent actions. He felt that they should be looking at repealing the PSU rather than the LOCE, which he saw as the key to changing the country's fortunes. He believed that repealing the LOCE was a solution to pre-dictatorship Chile, not today's society. According to him the current education system needed strong redirection in Chile to re-engage bored students, after the sound first four years of schooling. He felt everybody looked at the PSU success rates as the arbiter of Chile's fortunes, and that it was totally misleading. More emphasis needed to be placed on pre-graduation testing and vocational courses, as well as changing the current municipal curiculum priorities.

There is little doubt that the direct action of what ever form achieved something, even if the long term goals of the students are ultimately comprimised. What about the violent element, though? As someone who immensely dislikes violent action but does not reject violence outright as a defensive measure, I can't see how to justify it easily in this instance. No doubt it gained the students media attention and it also brought a quick direct response from the President, but continual NVDA would likely eventually have brought about the same negotiations. Without being present during the marches and rallies, I have no idea whether the students were provoked by the police or whether a fight was sought. Even then a provocation does not necessarily justify a violent response. It is true that the young people may have found it harder to contain their frustration than older individuals with more life experience. Certainly the police's response on the 30th May has been recognised even by the government as unacceptable. The campaign's successes seem to have been achieved by largely by NVDA. Perhaps I am wrong. Focusing on the strike probably paints a skewed picture of Santiago, which is certainly not a city on a knife edge. It's generally very safe and has a pleasant atmosphere.

Focusing on the strike probably paints a skewed picture of Santiago, which is certainly not a city on a knife edge. It's generally very safe and has a pleasant atmosphere.

Roberto, a friend we met through an internet music forum we use, kindly came to pick us up from the airport and took us up the famous Cerro San Cristobel - a public park on a massive hill overlooking Santiago. Here's the token shot of Santiago I mentioned at the start of the post! This photo was taken that day. The crowd by the marquee were celebrating a special mass. It was a quaint introduction to a new continent.

This Sunday I decided to run from our hostel up the winding road to touch the Virgin Mary at the top of the San Cristobel, which is over 850m high. It was a bit tough after a few weeks without much exercise, and I crawled the last few steps to the sacred mother in exhaustion. Fortunately, and by coincidence, a kind bloke I'd met over breakfast was sat on the steps leading up to the monument and with a look of pity he offered me some fresh pineapple. After some small talk between gasps of air and half-chewed pineapple, I headed back down the hill again. This is Pablo Neruda's dining room in Bellavista. I know very little about Latin American literature, apart from a couple of lectures and seminars at university on Borges. Indeed, I had only read any Gabriel Garcia Marquez a few weeks before we landed in Santiago. I was essentially unaware of Isabel Allende and her father. I'm a dumbass.

This is Pablo Neruda's dining room in Bellavista. I know very little about Latin American literature, apart from a couple of lectures and seminars at university on Borges. Indeed, I had only read any Gabriel Garcia Marquez a few weeks before we landed in Santiago. I was essentially unaware of Isabel Allende and her father. I'm a dumbass.

Whilst I work on finishing the Roberto Bolaño novel my Chilean friend leant me and get around to reading some Neruda myself, here's a bit about the man who is supposedly the person to inspire more people to read poetry than anyone since Shakespeare; he even read poetry to 70,000 people in the National Soccer Stadium in Santiago! He was highly political and a was forced to live as an exile by one government and a collaborator with another. The latter government was headed by the leftist Salvador Allende, Neruda's close friend, but it was brought down by Pinochet's military coup of 1973. Neruda was Communist Senator himself for a spell. His dubious respect for Stalin's dictatorship in Russia is also oft noted. If I am making him sound like an extreme South American version of Bono, I am describing him inadequately. Let me tell you about his house...